Fragrances today are mostly a fusion of ingredients taken from nature – or inspired by nature – together with the synthetics (man-made ingredients) that are used to make them last longer, ‘carry further’, or stay ‘true’, when worn on the skin.

Here, you can read about literally hundreds of the different perfume elements in use today. If you know which ingredient you want to read about, you can either input the name into our ‘search’ box (top right). Or click on a letter of the alphabet below – and it’ll take you to a collage of all the ingredients that start with that letter. Alternatively, let your eye travel over the scrolling, rolling collage below – and click on whatever takes your fancy: a visual ‘lucky dip’…

Castoreum

Beaver’s anal glands. Now who, exactly, first thought that an ingredient from the ‘castor sac’ (a gland near the beaver’s reproductive organs) would be just fantastic when bottled and dabbed onto the pulse-points…? (We often marvel at who must first have experimented with some of the more unusual elements in perfumery – and try to imagine some of the failed experiments, too…) Not surprisingly, this carnal, animalic note has since the beginning of the 20th Century – for ethical and environmental reasons –almost always been recreated synthetically: it’s really not on to kill an animal to extract a scented oil. (Although it was also used by physicians to treat fever, headache and hysteria.) But whatever the source, there’s no getting away from castoreum’s seriously musky sensuality, which also has a hint of fruitiness. Smelled neat (we’ve tried it: really not a good idea), it whiffs intensely of birch tar and leather; only when expertly blended does it soften and seduce, blending well with rose and oud in particular, and acting as an excellent ‘fixative’ for other notes. (‘Castor’, by the way, gets its name from the Greek word for beaver.)

Smell castoreum in:

Amouage Memoir Woman

Dior Diorama

Givenchy Ysatis

Guerlain Shalimar

Juliette Has A Gun Mad Madame

Juliette Has A Gun Midnight Oud

Hyacinth

One of spring’s favourite flowers, hyacinth gets its name from the Greek language: ‘flower of rain’. There’s a romantic (if slightly gory) Greek legend woven around hyacinth, actually: according to myth, the flower grew from the blood of Hyacinthus, a youth accidentally killed by Apollo – and even today, in Greece, the flower stands for ‘remembrance’. (In fact, Hyacinthus ambréeis originated in Syria, but it’s now grown ornamentally all over the world.)

Intensely green – green as spring itself – the smell of hyacinth develops as the flower blooms. In tight bud, the scent’s lightly, almost ethereally floral; as it opens, the scent becomes pumpingly potent and intoxicating (though still with that damp greenness). It’s widely used in white florals, and scents seeking to capture springtime-in-a-bottle, but because real hyacinth oil – produced by a process of extraction – is heart-stoppingly expensive, can’t-tell-it-from-real synthetic hyacinth notes are what perfumers turn to, nowadays.

Smell hyacinth in:

Goutal Paris Grand Amour

Goutal Paris Heure Exquise

Boucheron Bracelet Jaipur

Chanel Cristalle

Floris Edwardian Bouquet

Giorgio Armani Acqua di Gio

Guerlain Chamade

Yves Saint Laurent Y

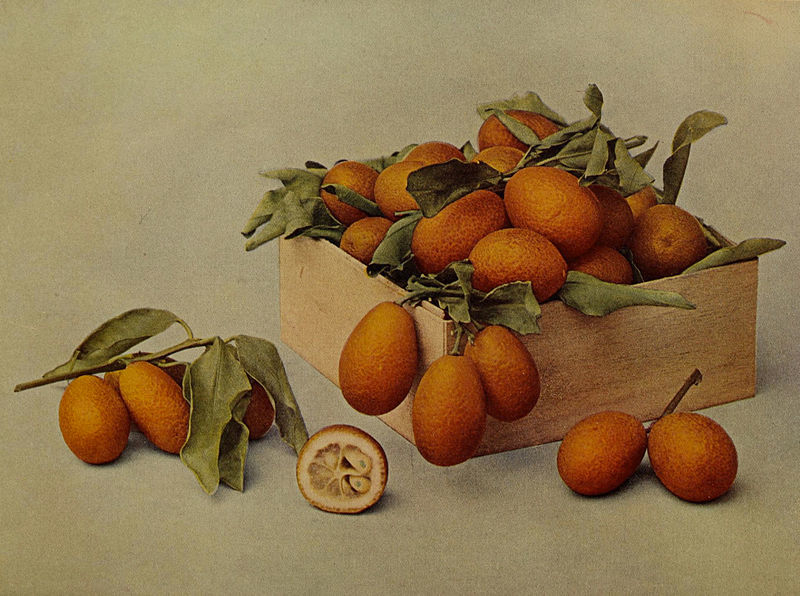

Bitter orange

Sometimes bitter orange is referred to ‘bigarade’ – but many of us know it best as the too-sour-to-suck-on Seville orange, used for making marmalade. The bitter orange tree is actually incredibly versatile, in perfumery: most neroli/orange blossom and petitgrain extracts come from this single tree, giving their soft/sweet/fresh qualities to countless delicious perfumes. (Petitgrain, which you can read about here, is extracted from the leaves, for instance.) But bitter orange is a fragrance note in its own right, widely used in eau de Colognes and chypre fragrances, as well as adding a whoosh of freshness to florals.

Smell bitter orange in:

Acqua di Parma Colonia Assoluta

Giorgio Armani Armani Code

Van Cleef & Arpels Cologne Noir

Bluebell

Ah, bluebells: those nodding, beautiful five-petalled spring flowers that seem so quintessentially English – but actually flourish anywhere from here to northern Spain, with over 500 species in all. (And although described as ‘blue’, they can be tinged from white to pink to deep, almost hyacinth in colour). These apparently delicate flowers - a.k.a. bellflowers – offer up an essential oil which has been described as reminiscent of a ‘clear spring day’. Stand in a bluebell wood, close your eyes and a delicate, green-floral haze will envelop and delight you: that’s what perfumers who work with bluebell are trying to recreate.

Smell bluebell in:

Penhaligon's Bluebell

Dyer’s greenweed

The clue’s in the name: this plant’s more widely used to dye clothing. (It’s also used in folk medicine.) With golden yellow pea-like flowers, the short, bushy shrub Genista tinctoria (which is a member of the broom family) flourishes in dry uplands, in the US. What does it smell of, in a fragrance? It’s dry, cool and bracken-like, adding a green feel to a scent.

Smell dyer’s greenweed in:

Boucheron Trouble

Verbena

Have you ever enjoyed fresh lemon verbena tea? We think there’s no more refreshing drink on the planet. The leaves of this flowering plant – which can grow to two or three metres – are deliciously lemony and fresh when rubbed, and give a cleanness and ‘uplifting’ freshness to scents. It’s the long leaves which are prized, rather than the tiny (and fleeting) white flowers. (Not to be confused, incidentally, with the type of verbena grown in Britain, which has no value in perfumery.)

Smell verbena in:

Acqua di Parma Colonia Assoluta

Goutal Eau du Sud

Boucheron Boucheron

Boucheron Jaïpur Bracelet

Givenchy Very Irresistible

Guerlain Eau de Cologne Impériale

Everlasting

Several names for this: Curry Plant, Herb of St. John, Immortelle (which you might know from the L’Occitane skincare range) - and botanically, Helichrysum augustifolium. All refer to small herb, which somehow manages to thrive in the most inhospitable, rocky, sun-baked zones in southern Europe. Amazingly, this grey-leafed toughie gives off a lovely, almost straw-like sweet scent, with hints of honey, tea, rose and chamomile - giving a flowery sweetness to perfumes…

Smell everlasting flower in:

Tonka

Amazingly, tonka bean is actually a member of the pea family. The seeds - from the fruit of the Dypterix Odorata tree - are black and wrinkled, and when grated give off pleasant aromas of sweet spice, vanilla, praline and almond. The scent actually comes from an aroma compound called coumarin: traditionally, tonka beans would be dried and cured in rum, producing small crystals of coumarin. (Today, a synthetic coumarin is widely used.) Very popular in contemporary perfumery – tonka’s sweetness goes beautifully in gourmand fragrances, as well as Ambrées – it was also used in the past for making pot pourri, to scent snuff, as well as being layered between clothes. (Now that we’d have loved to smell…)

Amazingly, tonka bean is actually a member of the pea family. The seeds - from the fruit of the Dypterix Odorata tree - are black and wrinkled, and when grated give off pleasant aromas of sweet spice, vanilla, praline and almond. The scent actually comes from an aroma compound called coumarin: traditionally, tonka beans would be dried and cured in rum, producing small crystals of coumarin. (Today, a synthetic coumarin is widely used.) Very popular in contemporary perfumery – tonka’s sweetness goes beautifully in gourmand fragrances, as well as Ambrées – it was also used in the past for making pot pourri, to scent snuff, as well as being layered between clothes. (Now that we’d have loved to smell…)

As perfumer Alienor Massenet explains, 'tonka is warm and smooth - but unlike vanilla, it can remind you of hay. I love to use it because it's big and powerful, very sensual. Used with an amber note, it creates a real addiction…' And Dior's Perfumer-Creator François Demachy adds: 'The tonka bean is a concentrate of sensations and aromas. It is dual, it has a multifarious seduction. Its milky sweetness invariably attracts. But it also reveals a soft yet surprising bitterness, when you taste it.'

Smell tonka in:

Bulgari Jasmin Noir

Chanel Coco

Chanel Coco Mademoiselle

Dior La Collection Privée Fève Délicieuse

Dior Addict

Dior J’Adore L’Or

Givenchy Ange ou Demon

Guerlain Shalimar

Guerlain Elixir Charnel Ambrée Brulant

Guerlain Samsara

Guerlain Tonka Impériale

Liz Earle Botanical Essence No. 15

Thierry Mugler Angel

Yves Saint Laurent Manifesto

Narcissus

Rich, floral, green, heady: like burying your nose in springtime itself. Or as perfumer Julie Massé explains to The Perfume Society: 'An opulent sensation of green-leaf, or the hissing of hot, wet summer lawns - a strangely intense and yet cool floral.'

Narcissus has been exciting perfumers for millennia. The Arabs used it in perfumery, then the Romans, who created a perfume called Narcissinum with the oil from what’s become one of our favourite modern flowers. In India, meanwhile, narcissus one of the oils applied to the body before prayer, along with jasmine, sandalwood and rose. (Nobody’s quite sure where the first flowers were grown; some believe it originated in Persia, and made its way to China via the Silk Route.)

There are hundreds of different species of Narcissi today – white, yellow, some with a touch of pink or orange (including our ‘everyday’ daffodil) – but not all are fragrant. The Pheasant’s Eye Narcissus (a.k.a. Poet’s Narcissus, or Narcissus poeticus) is native to Europe, and growers cultivate it in the Netherlands and the Grasse area of France, extracting an oil which smells like a blend of jasmine and hyacinth.

The scent can also be extracted from the so-pretty ‘bunched’ variety – Narcissus tazetta – is native to southern Europe and now also grown widely across Asia, the Middle East, north Africa, northern India, China and Japan. A third variety, Narcissus jonquil, can also be used, and in one form or another this beautiful ingredient is said to make its way into as much as 10% of modern fragrances - despite the fact that a staggering 500 kilos of flowers are needed to produce a kilo of ‘concrete’, or just 300 g of absolue, making it very pricy.

It’s so powerful, though, that only a touch is needed – and perfumers must proceed with caution: the scent in a closed room can be overwhelming. (Narcissus actually gets its name from the Greek word ‘narke’, which made its way into Roman language as ‘narce’: that meant ‘to be numb’, and alludes to the effect the oil can have.)

The supposed Greek legend linked with the flower is well-known: Narcissus was a handsome youth who fell in love with his own reflection, on seeing it in a pool. Unable to leave behind the beauty of his image, Narcissus died – to be replaced by this flower…

Smell narcissus in:

Boucheron Boucheron

Chanel Coco Noir

Chanel No. 19

Creed White Flowers

Dior Miss Dior

Donna Karan DKNY

Givenchy Ysatis

Guerlain Samsara

Lancôme Magie Noire

Maison Francis Kurkdjian Lumière Noire Pour Femme

Miller Harris Jasmin Vert

Van Cleef & Arpels First

Amaryllis

Anyone for ‘Naked Lady’? That’s an evocative name for a fragrance ingredient, if ever we heard one. But if you’ve ever received (or even grown) one of these bulbs (generally at Christmas), you’ll know what the name means: this trumpet-shaped flower really blooms when the foliage has died down. Bury your nose in an amaryllis (do mind the pollen!), and you might get whispers of a floral note, with fruity undertones – somewhere mid-way between a rose and a nectarine.

Smell amaryllis in:

Yves Saint Laurent Cinema

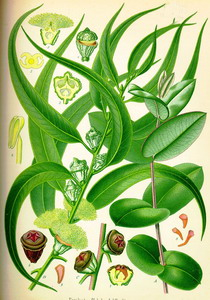

Tea

In a fragrance, tea’s almost as refreshing as in a china cup. Notes reminiscent of this favourite beverage – from the dried leaves of Camellia sinensis (seen in our photo growing on plantation slopes) - have made their way into quite a few sheer, uplifting fragrance creations in recent years, a trend kickstarted by Bulgari’s Eau Parfumée au Thé Vert. Sometimes the perfumer conjures up a black tea note, sometimes green – but the effect is always uplifting. According to experts, tea is set to be a key fragrance trend for spring/summer 2015.

In a fragrance, tea’s almost as refreshing as in a china cup. Notes reminiscent of this favourite beverage – from the dried leaves of Camellia sinensis (seen in our photo growing on plantation slopes) - have made their way into quite a few sheer, uplifting fragrance creations in recent years, a trend kickstarted by Bulgari’s Eau Parfumée au Thé Vert. Sometimes the perfumer conjures up a black tea note, sometimes green – but the effect is always uplifting. According to experts, tea is set to be a key fragrance trend for spring/summer 2015.

Smell tea in:

Bulgari Eau Parfumée au Thé Vert

Bulgari Mon Jasmin Noir L’Eau Exquise

L’Artisan Parfumeur Thé Pour Un Eté

Lancôme Aroma Tonic

Watermelon

Juicy watermelon has been quenching perfume-lovers thirst for fruity notes a lot, recently, thanks to the trend for fruity-florals. It’s summer in a bottle: very fresh, watery, sheer, but (unsurprisingly) sweet at the same time. Generally, it’s part of a cocktail of fruit notes – perhaps a dash of mango, a squirt of raspberry, a squeeze of guava…

Smell watermelon in:

Givenchy Fleur d’Interdit

Oakmoss

Oakmoss is among perfumers’ most beloved ingredients: an essential element of fragrances within the chypre family (which you can read more about here), in partnership with bergamot: it ‘anchors’ volatile notes. Its more romantic French name is ‘mousse de chêne, but this tight-curled plant – botanical name Evernia prunastri - is actually a lichen which grows on oaks throughout Europe and North Africa, only flourishing in unpolluted air. It can range in colour from light green to black depending on whether it’s dry or damp - and it smells a lot more beautiful than it looks.

Oakmoss smells earthy, and woody, sensual with hints of musk and amber and is really not like anything else in the perfumer’s ‘palette’ because it also works fantastically as a ‘fixative’ to give scent a longer life on the skin. As you might suspect, there’s a touch of damp forest floor to this material, too.

The use of oakmoss in perfumery goes back a long, long way. Coty’s Chypre perfume, in 1917, popularised this type of fragrance – but in fact, chypre scents, inspired by the island of Cyprus, had been beguiling people for centuries. For hundreds of years, from Roman times (that’s as far back as we know about) this style of perfume blended styrax, calamus and labdanum; in the Middle Ages, oak moss began to be added, to create ‘pastilles’ for burning.

But there’s one snag with this exquisite material: it’s been ‘blacklisted’ by the International Fragrance Association (IFRA) as a potential irritant, its use restricted by European regulation to 0.1% in perfume compositions that are applied to the skin – a restriction which has sent ‘noses’ into tailspins in labs across the world, as they were forced to remove or reduce this lynchpin ingredient in their often very famous formulations. Some ‘noses’ played around with ingredients like patchouli, or synthetic ‘imitations’ of oakmoss to try to achieve some of the same effects as this wonder of the natural scent world, but there’s no question that some favourite fragrances started not to smell like themselves.

Now, though, there’s a way through – which is glorious news for chypre-lovers everywhere. Through a process of ‘fractionation’ – separating the different elements of an individual ingredient, and removing the potential sensitiser – it’s possible to get an ingredient that’s much closer to the oakmoss we know and loved.

However, as Guerlain’s in-house perfumer Thierry Wasser explained to us, whenever something is removed from an ingredient through fractionation, ‘it leaves a hole’. Thierry’s stroke of genius was to plug the gap with a touch of celery seed, instead. Hey, presto: Mitsouko – probably the most famous chypre in the world still available today – is restored to its former glory. (And we just love the way that perfumers rise to challenges like this…)

PS Oakmoss has a near-relation, known as ‘tree moss’ - Evernia Furfuracea - which grows on pine trees, has a turpentine-y scent before it’s blended, and is also very highly-prized among perfumers.)

Smell oakmoss in:

Guerlain Mitsouko

Vetiver

‘A sack of potatoes’. That’s what legendary ‘nose’ Jean Kerléo told our Perfume Society co-founder Jo Fairley to close her eyes and think of, when smelling vetiver from a perfumer’s vial. And it’s so true: earthy, damp, woodsy and smoky all at the same time. Just like a hessian sack of potatoes that’s been left at the back of your grandfather’s shed, when you peel back the drawstring and b-r-e-a-t-h-e, actually.

It’s almost impossible to believe, actually, that this grounding, dry smell comes from the roots of a perennial grass – also known as Khus-khus grass - rather than a wood. Vetiveria zizanoides grows like crazy in marshy places and riverbanks in places that are drenched by high annual rainfall: countries like India, Brazil, Malaysia and the West Indies (Haitian vetiver is probably the most famous of its type). In some hot places, vetiver is woven into blinds and matting, which are not only wonderfully fragrant as the breeze wafts through them or they’re trodden underfoot: vetiver has cooling properties.

Used in perfumes since ancient times, vetiver’s more popular than ever and features very, very widely in the base of fragrances because it works brilliantly as a ‘fixative’ – and so far, nobody seems to have come up with a satisfactory synthetic alternative.

PS A relative of vetiver, Vetiveria nigritina, is also found in the Saharan areas of Africa, and is used to perfume clothes and fabrics – but it doesn’t make its way into the perfumes we wear.

Smell vetiver in:

Creed Vetiver

Frederic Malle Vetiver Extraordinaire

Guerlain Vetiver

Lancôme Hypnôse

Chanel Les Exclusifs de Chanel Sycomore

Escentric Molecules Molecule 03

Heliotrope

When you smell something sweet, powdery, fluffy-little-cloud-like in a perfume, chances are there’s a touch of heliotrope in there. Or do you get a whiff of almond…? Maybe that’s chameleon-like heliotrope, in the blend… A touch of vanilla? That could be heliotrope, too.

The use of this gloriously purple-coloured plant in perfumery goes right the way back to Ancient Egypt. Technically, heliotrope can be still extracted by maceration (or through solvent extraction, the modern form of enfleurage), an echo of those times - but today it’s synthetic heliotropin – read about it here – which perfumers rely on.

Heliotrope’s teamed with violets and iris for a talcum-powdery, lipstick-esque sweetness – but as you may now have guessed, it’s actually very versatile, becoming almost mouthwatering when used alongside bitter almond, each ingredient turbo-charging the other’s marzipan-ish qualities. Put it with frangipani or vanilla, though, and their mutual sweetness comes out… (If you were to look under a microscope, vanilla essential oil actually contains a little heliotropin in its make-up.) You’ll find heliotrope in many legendary Guerlain fragrances, as well as countless contemporary ‘gourmand’ scents.

An annual-flowering member of the borage family, also known as ‘cherry pie flower’, you’ll often find Heliotropium arborescens on sale in nurseries and garden centres for summer bedding (and you can create a wonderfully scented display with the plants, which butterflies will also love).

Smell heliotrope in:

Guerlain L'Heure Bleue

Linalool

Linalool is a fragrance compound found in rosewood oil and other essential oils, including petitgrain, coriander and lavender. Its spicy-floral character works perfectly in many different florals – though in small quantities; a known sensitiser for a very small percentage of wearers, it’s one of the ingredients which perfume houses must compulsorily list on a label.

Boronia

A really expensive fragrance material – one of the priciest in the world, in fact - boronia comes from a fragrant shrub native to Australia. Perfumer and author Mandy Aftel calls it ‘as close to heaven as we are likely to get’, telling us it’s reminiscent of raspberry, apricot, violet and yellow freesia. (Technically, boronia is a member of the citrus family.) It’s delectably intoxicating, in fragrances – and perfumers love to blend it with sandalwood, bergamot, clary sage and other floral notes. Find it mostly in chypre and fougère creations.

Smell boronia in:

Ralph Lauren Ralph

Bacon

Bacon…? In a fragrance…? Yes, really: this salty, smoky breakfast food has been used in synthetic form as a ‘novel’ (very novel) perfume ingredient in John Leydon’s Fargginay fragrance brand, in a specific bacōn collection. Nowadays, perfumers have to work ever-harder to create a point of difference. Sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn’t. Sniff out a bacon fragrance for yourself, and make up your own mind…!

Smell bacon in:

Flax

Fields of flax are heart-stoppingly – maybe even car-stoppingly – beautiful, with pale blue flowers wafting in the breeze. Perfumery isn’t the most familiar use of flax (a.k.a. Linum usitatissimum): it gives us both linen and linseed (highly nutritious, and also terrific as an oil applied to wooden furniture to keep the elements at bay). But flax has also been used in perfumery as long ago as Egyptian times, as a base note – mildly nutty in character.

Smell flax in:

Bvlgari BLV

Bergamot

Bergamot orange is the fragrant citrus fruit of the Citrus bergamia, a small evergreen tree which blossoms during the winter. The fruit is the size of an orange, with a yellow-green colour similar to a lemon. The juice tastes less sour than lemon, but more bitter than grapefruit – which explains why bergamot has become known for its aromatic essential oil, rather than as something we eat for breakfast... (Although bergamot is used in Earl Grey tea…)

Its scent is fruity-sweet with mild spicy hints, and you’ll encounter it as a top note in compositions within most of the fragrance families – male and female. In fact, it’s used in different proportions in almost all modern perfumes - particularly within chypre and fougère fragrance categories, giving an initial fresh, airy, uplifting quality. (No surprise that in aromatherapy, bergamot is actually used to treat depression…) For perfumers, it’s invaluable for helping to blend notes into a single bouquet, and fix them there…

Its use goes back for centuries: bergamot was famously known to be a component of the original Eau de Cologne, developed in Germany by J.M. Farina in the 17th Century. For centuries, the essential oil of bergamot has had a close link to perfumery and scent, even used to scent small papier-mâché boxes for keeping small precious mementos - like locks of hair and ‘love letters.

The word bergamot derives from bergomotta in Italian and from Bergamum, a town in Italy. But references also exist, indicating the name comes from the Turkish word beg-armudi – which translates as ‘prince's pear’ or ‘prince of pears’…

Bergamot is commercially grown in southern Calabria in southern Italy, where more than 80% of the essential oil is produced – by zesting the rind. It’s also grown in southern France and in Côte d'Ivoire for the essential oil (and in in southern Turkey for its marmalade…)

Smell bergamot in:

Miller Harris Terre de Bois

Karo-karounde

This flowering shrub pulses out its potent scent very powerfully, in its native west Africa. It produces an essential oil that’s reminiscent of jasmine, though a little woodier, a touch spicier and more herbal. It goes brilliantly in tuberose compositions, and beautifully enhances chypres. And depending on its ripeness, it can give hints of chocolate, or ripe fruit. Karo-karounde (also sometimes written as karo-karunde) is considered to be an aphrodisiac and is used in the rituals of sexual magic, in the Congo!

Smell karo-karounde in:

Water

Can a fragrance really smell of water? Issey Miyake would like us to think so: his iconic L’Eau d’Issey was created to conjure up the purity and clarity of water. (It was one of the first ‘juices’, or perfumes, to be almost as clear as fresh water in colour, too.) Mostly, ‘water’ in fragrance ingredient terms has come to mean an oceanic, salty/seawater vibe – which is actually recreated through the use of a complicated blend of synthetics. The idea is that ‘watery’ fragrances should actually should smell ‘breezy’, ‘outdoorsy’, like the mist that’s in the air when we take a walk on a beach with the surf crashing against the sand. (Because of course if you simply filled a bottle with water, you’d end up with something with no more of a scent than Perrier or Evian.)

Smell water (or rather ‘ozonic’ notes) in:

Issey Miyake L’Eau d’Issey

Brown sugar

As you’d imagine, brown sugar adds sweetness to our perfumes in just the same way as it does to cereals, cakes, candies. Sugar was once a precious commodity, a delicacy. Now, as we know, it’s in countless foods, and most of us have a love-hate relationship with the stuff. But perfume-wise, sugar’s star is in the ascendant in line with the boom in gourmand compositions, adding almost a touch of ‘booziness’. Great with vanilla. (Just like in baking.) But with zero calories…

Smell brown sugar in:

Penhaligon's Equinox Bloom

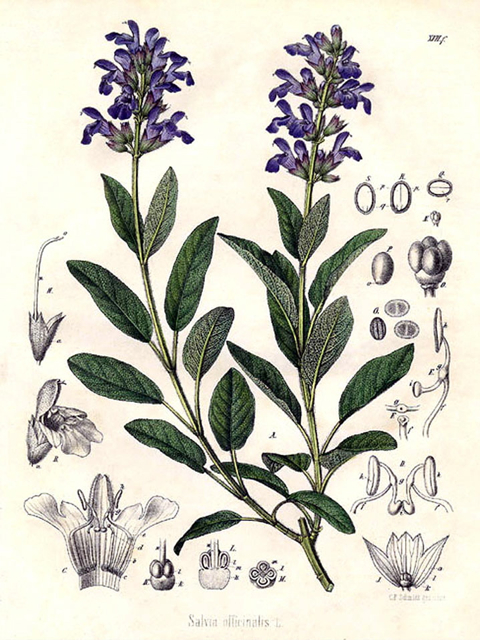

Rosemary

Pungent, lavender-like, aromatic: nothing smells quite like rosemary. (Well, camphor and eucalyptus and even mint smell a little bit like rosemary - but most of us could still make out its distinctive ‘whoosh’ if blindfolded). Julie Massé, whose many fragrance creations include Shay & Blue's portfolio, explains: 'I use it to give a Mediterranean sensation - to create the impression of a cocktail of herbs...'

Because of those herby qualities, rosemary’s used with only the lightest touch in female perfumes, though more widely in so-called ‘men’s scents’. Its use actually goes way, way back: the Ancient Greeks burned rosemary as incense, and it became part of religious ceremony (and even exorcisms): the smoke of rosemary is deeply cleansing. Rosemary wasn’t known to the Arab perfumers, but it started to be distilled as an oil in the 15th Century, and was a key ingredient in one of the first ‘modern’ perfumes, Hungary Water.

A woody evergreen, rosemary has super-fragrant needle-like leaves, and white, purple, blue or pink flowers, depending on the variety. It’s seriously low-maintenance: the name ‘rosemary’ comes from the Latin for ‘dew’ (ros) and ‘sea’ (marinus), because all it needs is the humidity of a sea breeze to flourish. Today, no home herb garden’s complete without rosemary – which was once planted to repel witches. This somehow led to the idea that where rosemary grew outside a house, it symbolised that a woman ruled the household. (And around the time of the 16th Century, not a few men could apparently be found ripping out rosemary bushes to show that they, not their wives, were boss.)

It’s also said to be good for memory (as well as for stimulating hair growth), and is used symbolically in weddings, funerals and war commemorations in the UK and Australia: ‘Rosemary for remembrance’.

Smell rosemary in:

Dior La Collection Couturier Parfumeur Granville

Diptyque L’Eau de Hesperides

Guerlain Jicky

Lancôme O de Lancôme

Miller Harris Fleur de Sel

Yardley English Lavender

Orris root

A hugely precious ingredient, this – with a heart-stopping price-tag. That’s because the orris – from the rhizomes, or ‘bulbs’ of the iris plant – are odourless when harvested, and take three or four years to mature. (They’re left in a cool, dry place, and need protection against fungus and insect attack which would destroy the producer’s valuable harvest.)

Iris, or orris, has lent its sweetness to perfumery for centuries – as far back as Ancient Rome and Greece, or perhaps even beyond. Back then, it was made into hair and face powders, placed into pomanders, and was the basis for delicious perfumed sachets for wearing on the body. (An idea we’d rather like to see revived...) Iris has long been a symbol of majesty and power, too.

The most sought-after type of orris come from the Iris pallida variety, which flourishes in the warmth of the Mediterranean. Florentine iris ticks perfumers’ boxes, too. After those rhizomes have aged, they’re powdered – and then steam-distilled, producing orris oil, which solidifies into something known as ‘orris butter’ (or ‘orris concrete’), because of its oily, yellow texture and appearance.

It's been highly fashionable in fragrances for the past few years: sweet, soft, powdery, suede-like – rather like violets, which we tend to be more familiar with as a scent. Actually, iris runs the spectrum from sweet to earthy: it also works brilliantly to ‘fix’ other ingredients, giving a more lasting quality to florals and base notes. Often, only the lightest touch of orris is needed in fragrances – but ‘noses’ wouldn’t be without it, for the world.

Smell orris root in:

Acqua di Parma Iris Nobile

Chanel Les Exclusifs 28 La Paula

Frederic Malle Iris Poudre

Guerlain Après l’Ondée

Guerlain Samsara

Jovoy Paris Poudre

Prada Infusion d’Iris

Yves Saint Laurent Paris

Edelweiss

Those of a certain age will be most familiar with edelweiss as the name of a song crooned by Christopher Plummer in the movie of The Sound of Music. Off-screen, this flowering plant flourishes further afield than the European alps, where it’s a protected species: edelweiss is nowadays most commonly found in Javanese mountain regions. It smells sweet, but not as cloying as hyacinth. A short-lived perennial with beautiful white flowers, edelweiss has long been valued as a medicinal plant – but in fragrance, it’s not actually used very widely. Edelweiss does make an appearance in a couple of Swiss Army fragrances – but it’s there, we suspect, more to make a link that evokes the wide open spaces of Switzerland than for the note itself.

Smell edelweiss in:

Wormwood

With the current frenzy for exotic cocktails, chances are you may tasted wormwood (Artemisia absinthum) – the key ingredient in absinthe, a drink that was for years banned in France but is now very much in vogue. (It’s also used in vermouth.) As a medicinal, use of this exceedingly bitter herb goes all the way back to Egypt. (It helps to dispel parasites – hence its name…) In fragrances, wormwood is also bitter and green – and so used with the lightest touch, generally (in men’s but also women’s scents), because it’s pungent and intensely herby. (See also Artemisia).

Smell wormwood in:

Amouage Memoir Woman

Histoire de Parfums 1889 Moulin Rouge

Metal

Nobody grinds up metal and adds it to a perfume blend – but the genius of perfumers is that they nevertheless have a way of conjuring up hints of iron and steel in a bottle, as an evocative ‘fantasy’ note. (Sometimes, they’ll turn to synthetic iris to create that cool, almost sterile effect…)

Smell metal in:

Comme des Garçons Odeur 53

Penhaligon’s Sartorial

Marigold

Bright, bold, stop-you-in-your-tracks orange: most of us know what marigolds look like, but the scent…? Mix bitter herbs, ripe apples and green leaves.

Marigolds – the name comes from the phrase ‘Mary’s gold’, and refers to the Virgin Mary – are members of the sunflower family, grown throughout the world. There are actually two types, which share the same ‘marigold’ umbrella name: Calendula officinalis, and Tagetes Glandulifera (the French marigold, a.k.a. Indian Carnation). Calendula blossoms, with their musky pungency, are used to produce essential oil through steam distillation; tagetes oil comes from the seeds of that plant – though in terms of what they deliver to a perfume composition, they’re pretty interchangeable.

Although marigold is more widely used in ‘men’s perfumery’, a handful of well-known feminine fragrances do feature flashes of this unusual note, for an intriguing twist…

Smell marigold in:

Boucheron Boucheron

Avocado

This yummiest of fruits originates from Central Mexico (‘guacamole-land’!). And are you ready for the explanation of the name…? ‘Avocado’ comes from ‘aquacate’ – which apparently derives from the Aztec for testicle. (A reference to the shape of the fruit.) It’s very rarely used as a fragrance note – more widely, for the brilliant skin-smoothing, nourishing properties of avocado oil, in body products and facial care.

But just sometimes, you’ll catch a whisper of avocado in perfumery: it has a green, slightly sweet, vegetal quality…

Smell avocado in:

Versace Versus Time for Relax

Frangipani

Exquisitely exotic, heady, tropical: frangipani is sultry hot nights – and sexy, sexy, sexy. Frangipani isn’t actually the name of a plant, though: it’s an ingredient from plumeira flowers, which have a gardenia-like scent: soft, peachy, creamy, fruity. And did we say sexy…? It pumps out its fragrance at night, to attract insects. (And seems to work equally well on members of the opposite sex.) Perhaps unsurprisingly, frangipani pairs well with ingredients from tropical fruits, and coconut.

There’s an intriguing back story to the naming of this plant, meanwhile. Once upon a time, frangipani was the name of an actual perfume – produced by an aristocratic Roman Renaissance family by the name of Frangipani, and created by mixing orris (iris root), spices, civet and musk. (Those last two are outlawed in modern perfumery, of course.) Wine was added to those ingredients to make a long-lasting perfume, which was also used to scent gloves – known as ‘Frangipani gloves’.

When a French colonist later came upon a plant in the West Indies that smelled just like that perfume – the Plumeira alba plant – he named it ‘frangipani’. Which is definitely the only instance of a plant getting its name from an actual fragrance: it’s far more usually the other way round…

Smell frangipani in:

Kenzo Kenzo Amour Florale

Elder

It takes a lot of elderflower to produce a little essential oil – so this note is usually recreated synthetically, to evoke that sweet, honey-like, floral-herby scent of this hedgerow plant. The Sambucus nigra flowers – white, frothy, umbrella-like – actually go much further when they’re used for making drinks (elderflower’s a popular cordial). They’re also often left to produce fruit, which can be infused to extract an intense berry scent. Mostly, though, when you see elder listed as an ingredient, that’ll be a synthetic version.

Black pepper

Hot, fresh, almost tingly to sniff: this top note perks up many masculine and some female scents, adding instant brightness.

Hot, fresh, almost tingly to sniff: this top note perks up many masculine and some female scents, adding instant brightness.

Black pepper’s variously referred to as ‘the King of Spices’, or even black gold, and it’s been traded since the Roman empire, when the ‘spice routes’ to China and India opened up. (Literally, it was a medium of exchange, a form of money.) Everyone knows black pepper as a food ingredient: it now spices up meals all over the world - it's actually the most widely-used spice on the planet. (That’s because it also helps digestion, as well as enhancing flavours.)

This flowering vine was originally native to the south of India, where it’s long been used in Ayurvedic medicine. Once upon a time, black pepper’s value was on a par with gold – hence the nickname – and only the rich could enjoy it. (Not only was black pepper ground onto food, though: it found its way into spells and was used as an amulet to protect against disease and other threats.)

In perfumery, the not-quite-ripe peppercorns of the Piper nigrum vine are dried, crushed and steam-distilled to create an intensely-fragrant oil which is surprisingly complex: as well as delivering a burst of heat, it’s surprisingly fresh – and woody, too, blending beautifully with citrus fruits like lemon, as well as aromatics including lavender, ginger, clove, coriander and geranium. We love the idea that (as fragrance writer Mandy Aftel puts it), black pepper isn’t just thought to stimulate the mind, but to ‘warm the indifferent heart’…

Perfumer Andy Tauer tells us he's still experimenting with it, as an ingredient. 'So far, I have used black pepper only once in my perfumes - together with a bundle of citrus and vetiver. This combo is unbeatable. The brightness and sparkling fuzziness of citrus, the damp woody, earthy brown vetiver and the sharpness of pepper fit like Coke, fries and burger. Pepper, is metallic and spiky, sharp. But compared to cardamom it is actually easier to handle - like a poodle compared to a bull dog. Both are lovely, but the poodle mostly just hops and jumps.'

Smell black pepper in:

Argentum Magician

Diptyque Ofresia

Kingdom Scotland Metamorphic

Molton Brown Re-charge Black Pepper

Blueberry

Refreshing, subtly sweet – or positively jam-like: blueberry has different facets which perfumers have the power to play up. (Especially now fruity-florals are so popular in our fragrance wardrobes: blueberries work really well to enhance floral perfumes.) The flowering Vaccinum myrtillus shrub that gives us blueberries is native to north America, but now grown around the world: its nutritious berries aren’t just delish, they’re packed with health-boosting antioxidants. And they smell lovely. (Close your eyes, bite a blueberry open and inhale before popping one in your mouth, next time.)

Smell blueberry in:

Lalique Amethyst

Rose

A fragrance without roses is almost as unthinkable as a love affair without kisses. Not only are roses the most romantic of flowers to look at: they’re an absolute cornerstone of perfumery – the most important flower of all, from the point of view of a nose: sometimes powdery, sometimes woody, musky, myrrh-y, clove-like, sometimes fruity, or just blowsily feminine – but always, intensely romantic. Roses are said to feature in at least 75% of modern feminine fragrances, and at least 10% of all men’s perfumes.

Today's savvy perfumers, however, are far from the first to recognise the sheer sensual potential of this 'Queen of Flowers'. In Classic myth, the rose was linked both with the Greek goddess Aphrodite and her Roman counterpart, Venus. When Cleopatra welcomed Mark Antony to her boudoir, her bed was strewn with these aphrodisiac blooms and the floor hidden under a foot and a half of fresh-picked petals. Who could resist rolling around in that? Certainly no hot-blooded Roman, homesick for a city where rosewater bubbled through the fountains, awnings soaked in rose oil shielded VIPs in public amphitheatres from the baking sun, pillows and mattresses were stuffed with rosepetals (the better to propel the weary towards dreamland) and where rose garlands were the ultimate Roman must-have status symbol. The same flowers turned up in delicately-scented puddings, love potions and medicines. At one bacchanale, the Emperor Nero, clearly no tightwad, had silver pipes installed so guests could be spritzed with rosewater between courses.

The fragrant liquid which refreshed Roman guests and was flung up by fountains all around town, however, was rosewater - the water in which roses have been steeped, then discarded. In reality, rosewater is the poor relation of the ‘true’ rose scent, from the oil that’s so essential a component of the perfumes which today send our senses into a delicious spin.

Rose essential oil can come in the form of rose otto (also known as attar of roses), or rose aboslute. Rose otto’s extracted via steam distillation, while the more precious rose absolute, via solvent extraction, or CO2 extraction.

The roses most commonly used in perfumery are the Turkish rose, the Damask (or Damascene rose) and Rosa Centifolia (the ‘hundred-leafed rose’), which is grown around Grasse in the south of France, and generally considered to produce the highest quality rose absolute. (This rose is also known as Rose de Mai, because it generally blooms in the month of May, and – romantically – ‘the painter’s rose’, because it features in many works of the old masters.)

Around 70% of the rose oil in the world comes from Bulgaria; other significant producers are Turkey, Iran and Morocco, and precious, limited quantities from Grasse. The task of the rose-picker is to pick the dew-drenched blooms before 10 a.m. at the latest, when the sun evaporates their exquisite magic. So fast does the rose fade, in fact, that some farmers in Turkey and Bulgaria transport their own copper stills to the fields, heating them on the spot over wood fires to distill the precious Damask Rose oil, which separates from the water when heated in only the tiniest of quantities: 170 rose flowers are said to relinquish but a single drop.

Smell rose in:

Goutal Paris Rose Absolue

Maison Francis Kurkdjian À la rose

Editions de Parfums Frédéric Malle Lipstick Rose

Goutal Rose Pompon

Acqua di Parma Rosa Nobile

Floris A Rose For...

Diptyque Opône

Floral Street Neon Rose

Lancôme Trésor

Yves Saint Laurent Paris

Thyme

Thyme gets its name from the Greek word meaning ‘to fumingate’ – and its fragrant use goes back that far: the Greeks used it as a powerful incense in their temples (it was even thought to repel snakes), while the Arab perfumers also used it in their recipes. There are many different varieties of this Mediterranean shrub, but today it’s the flower tops of ‘Garden Thyme’ (a.k.a. ‘French Thyme’), or Thymus vulgaris, from which most of the essential oil is steam-distilled. It’s spicy, aromatic – and surprisingly leathery, in a perfume. A pinch of thyme is more likely to be found in a ‘masculine’ fragrance than something targeted at women, though it also makes its way into quite a few unisex Colognes.

Smell thyme in:

Maison Francis Kurkdjian Absolue Pour le Matin

Maison Francis Kurkdjian Cologne Pour le Matin

Miller Harris Fleur de Sel

Wisteria

Captured in a bottle, wisteria’s as lush and beautiful as when it scampers up the outside of a house or over a pergola, garlanding them with multi-flowered, hanging ‘racemes’. There’s a touch of lilac about this feminine perfume note – but a slightly spicy undertone that adds intrigue, at the same time, reminiscent of the cloviness of carnation.

Smell wisteria in:

Versace Versace

Elecampane

The roots of this plant – also known as horse-heal (and officially Inula helenium) – can be distilled to produce an essential oil, with a minty, violet-like scent. (Over the centuries, it’s also been valued as a medicinal and was actually recommended by the famous herbalist John Gerard; elecampane has been prescribed for shortness of breath and water retention.) The dried roots also make their way into pot pourri.

Suede

No, not really suede – but perfumers can recreate the suede’s enveloping sensuality, in perfumery using synthetic ingredients. It’s fascinating to us how perfumes – which are invisible – can have a ‘texture’, but the fragrances listed below really do give a sense of that, as they cocoon you with their musky, woody, velvety, leathery qualities.

Smell suede in:

Donna Karan Cashmere Mist

Donna Karan DKNY

Donna Karan Donna Karan

Guerlain Cuit Beluga

Lacoste Pour Femme

Lilac

The powdery sweetness of lilacs fill the air in suburban streets and parks in late spring: short-lived, but utterly beautiful, with their pollen-y, jasmine-like softness, and tantalising hints of almond and roses. As perfumer Andy Tauer tells The Perfume Society, 'Lilac in perfumes is the note of spring, the promise of summer.'

The powdery sweetness of lilacs fill the air in suburban streets and parks in late spring: short-lived, but utterly beautiful, with their pollen-y, jasmine-like softness, and tantalising hints of almond and roses. As perfumer Andy Tauer tells The Perfume Society, 'Lilac in perfumes is the note of spring, the promise of summer.'

Lilacs were introduced into Europe via Spain around the 16th Century, from the Arabs. The early fragrant use of the flowers was in pomanders. Our favourite lilac legend, though, is that the deep floral fragrance was believed in Celtic cultures to transport humans into fairyland and the spiritual world.

A fragrant oil can be solvent-extracted from the foamy blossoms of the Syringa plant (it comes from the Greek, meaning ‘pipe: shepherds made flutes from lilac wood and it was believed that whoever heard their music would never forget it). Nowadays, a synthetic form of lilac’s often used in contemporary perfumery, as it’s possible to recreate the tender natural fragrance perfectly, more reliably – and year round.

Do smell deep, though, and see if you can detect intrigue beneath the soft surface. Because Andy observes: 'My white lilac blooms early, due to an early spring in Zurich. I am convinced that I can detect a hidden note of car exhaust, modern car, there. How cool is that? It goes to show: flowers are more than what we see. I love them for that.'

Smell lilac in:

Cristobal Balenciaga Le Dix

Frederic Malle En Passant

Givenchy Le de Givenchy

Guerlain Chamade

Guerlain Champs Elysées

Guerlain Idylle

Guerlain Mitsouko

Guerlain Nahéma

Versace Versace

Freesia

It’s no surprise that freesias are favourite flowers, for many of us: these delicate, multi-coloured flowers smell so radiantly sweet and airy, with an almost nose-tingling freshness – and a hint of citrus in there somewhere, too.

Yet try as they might, perfumers have never been able to capture the scent of freesias. As perfumer Alienor Massenet explains, 'Freesia in perfumery is an imaginary reconstitution - but the smell is gorgeous.' So: it’s produced synthetically, adding a hint of green sweetness – and airiness – to fragrance creations. Alienor adds: 'It's smells like tea, actually.' Freesia works perfectly to complement lily of the valley, peony, magnolia, but is rarely the shining star of a perfume itself.

Freesias get their name from a German doctor, from Kiel in Germany - Friedrich Heinrich Theodor Freese (1795-1876). A plant collector (who went by the equally glorious German name Christian Friedrich Ecklon) honoured his friend by calling the flower (which originated in Africa) ‘freesia’.

We love this quote about freesias that we first found on the perfume website Fragrantica, meanwhile.

'The happiness of that afternoon was already fixed in her mind, and always would the scent of freesia return it to her mental sight, for among the roses and violets and lilies and wall-lowers, the smell of freesia penetrated, as a melody stands out from its accompaniment, and gave her the most pleasure.' (Hugh de Sélincourt wrote that, in The Way Things Happen.)

Freesia notes contain a certain amount of linalool, which is a known sensitiser (and listed on perfume packaging as a caution to the sensitive).

Smell freesia in:

Diptyque Ofrésia

Ylang ylang

Once upon a time, ylang ylang – a tendrilled tropical flower which blossoms on a tall tree – was known as ‘poor man’s jasmine’ (because it has many similarities, scent-wise). But not any more: this seriously exotic, intense, rich fragrance note is at the top of the price scale for ingredients – though even so, it’s still present in as much as 40% of quality perfume creations. Ylang ylang famously clambers round the heart of some of the most beloved fragrances in the world, including the best-known of all: Chanel No. 5. (The perfume’s creator is on record as saying that without ylang-ylang in the formula, he couldn’t have used such a high dose of the champagne-like aldehydes that give No. 5 its airy overture: it ‘tethers’ the creation). It’s generally recognised to be one of the more ‘aphrodisiac’, sensual note in the perfumer’s box of tricks. 'It's often used to surround jasmine, in white floral bouquets,' notes perfumer Alienor Massenet. 'It has an almost cinnamon quality, yet is very feminine.'

Ylang yang is also luscious, buttery, a little apricot-y and – when smelled ‘neat’ – is a tad medicinal, too. (In aromatherapy, it dispels tension.) The note is steam-distilled or solvent-extracted from the creamy flowers of the tall plant (Cananga odorata) – it can be either a tree or a vine, growing to almost 20 metres. Ylang ylang grows in the Phillipines, Java, Réunion and the Comoro Islands. Most of us are unlikely to smell it growing wild, but apparently it’s deliciously, delicately sweet, in flower form.

But why the high price? It takes around 400 kilos of flowers to produce one kilo of essential oil, and each tree provides around 10 kilos of flowers a year. Go figure.

PS Say it ‘ill-ang ill-ang’.

Smell ylang ylang in:

Chanel No. 5

Dior Diorissimo

Maison Francis Kurkdjian APOM Pour Femme

Stephanotis

The waxy flowers of this tender twining shrub – also known as Madagascar Jasmine or Creeping Tuberose – are traditionally used in wedding bouquets and headdresses: romantic, sweet, and (yes) a little like tuberose and jasmine. Stephanotis generally appears as part of a bigger bouquet of blowsy, hypnotic white florals.

Smell stephanotis in:

Dandelion

Gardeners everywhere probably wish that every dandelion on the planet could be weeded out and imprisoned in a perfume bottle. Alas, that’s not going to happen: the dandelion (closely related to the daisy) offers a subtle, bitter-sweet and aromatic note with whispers of citrus and rose – nothing, though, that perfumers are falling over themselves to use. Just like daisies, the yellow flowers open at daybreak, and bed down for the night.

Smell dandelion in:

Shay & Blue Dandelion Fig

Styrax

Also known as ‘storax’, both names for benzoin. In common with balsam of Peru and balsam of tolu, this is an oil – tapped from a tree (Styrax benzoin, hence the two names), after deliberately damaging the bark.

Also known as ‘storax’, both names for benzoin. In common with balsam of Peru and balsam of tolu, this is an oil – tapped from a tree (Styrax benzoin, hence the two names), after deliberately damaging the bark.

It was first described in the 14th Century; the Arabs called benzoin ‘frankincense of Java’, and it’s had a seriously long tradition of use in pomanders, pot pourri, incense and soaps. (Rather usefully, benzoin multi-tasks as an antiseptic and an inhalant, as well as a stypic, i.e. it actually stops minor wounds bleeding.) Benzoin gives ‘body’ to many perfumes (it’s especially widely-used in ambrées) and is sweetly seductive, very reminiscent of vanilla.

Adds perfumer Andy Tauer, 'Styrax actually comes in two forms, which give different effects. The first is resinoid, which is perfect with lavender. Don´t ask me why but it seems to fix it perfectly and it calms the hyperactive lavender. The other type is leathery with woody smoky, undertones - not like birch tar, though, with its association of smoked sausages and campfires in October with wet wood. It is more the leather that you expect your gloves to exhale. I love the warm leather tones of this quality of styrax - but it needs careful handling, though.'

Smell styrax benzoin in:

Chanel Coromandel

Givenchy Pi

Prada No. 9 Benjoin

Yves Saint Laurent Opium

Lily

There are over 100 species of lily and it always slightly breaks our heart to buy a bunch and discover: they’re not always scented… But many varieties – the Madonna lily (named as a nod to the purity of the Madonna), the Casablanca Lily and the Ambrée/Stargazer Lily most definitely are, and their subtly different scents are all caaptured in perfumes: intoxicating, heady, rich and sweet, reminding us of jasmine or tuberose. (‘Headspace’ technology is usually used to capture the scent: the air around the bloom is analysed, and the aroma compounds flawlessly recreated in the lab.)

Lilies have been used in perfumery since ancient times: they were very well-loved in Egypt, as part of a perfumed ointment ‘based on the flowers of 2000 lilies’, while the ancient Greeks used Madonna lilies to make a perfume called Susinon.

They’re wonderful in the home, possibly the perfume-lover’s must-have bloom. So long as the lily flowers you buy are indeed fragrant, they’ll pump their sweetness into the air without fading for a couple of weeks at a time…

Smell lily in:

Cartier Baiser Volé

Dior Diorissimo

Frederic Malle Lys Mediteranée

Ginger

Bracing, uplifting and almost nose-tinglingly spicy, ginger pairs beautifully with vanilla, woody notes and citrus, as well as white flowers like jasmine and neroli. This spice is used quite widely in perfumery – as well as a wide range of foods and medicines, too, produced everywhere from South America to Malaysia, the Caribbean, Japan and Africa.

Many of us are familiar with the beige-skinned, yellow-fleshed fresh spice, which adds pungency to cooking – as the Romans, who first imported it, discovered. Those same roots we love to spice up our food with – rhizomes, to use the perfume world’s word for them – can be steam-distilled to produce this useful scented oil.

We’re generally not so familiar with the flowers – which aren’t any help to perfumers at all – but aren’t they gorgeous? (Interior decorators, as well as perfumers, also love ginger – for the sheer architecture of the plants.)

Smell ginger in:

Chanel Bois des Iles

L’Artisan Parfumeur Tea for Two

Licorice

Do you love licorice? Do you hate it? Most of us fall into one camp or the other, but even if you’re not a licorice-licker, you may still find its subtle aniseed-y, almost caramel-y note in perfumery intriguing and beguiling. It’s used to beautiful effect in gourmand fragrances, and blends with woods and earthy notes, too.

Do you love licorice? Do you hate it? Most of us fall into one camp or the other, but even if you’re not a licorice-licker, you may still find its subtle aniseed-y, almost caramel-y note in perfumery intriguing and beguiling. It’s used to beautiful effect in gourmand fragrances, and blends with woods and earthy notes, too.

The word ‘licorice’ (or liquorice) comes from the Old French licoresse, and originally from the Greek meaning ‘sweet root’ (it really is, if you’ve ever chewed a licorice stick). It’s been around for thousands of years: archaeologists found Roman licorice along Hadrian’s Wall, and it was also uncovered in the pyramids. Though reminiscent of fennel and aniseed, Glycyrrhiza glabra is not actually related to them, however.

But did you know that licorce is used in love spells…? Sprinkled in the footprints of a lover, it’s said to keep them from wandering. And in a fragrance…? Equally bewitching.

Smell licorice in:

Bulgari Jasmin Noir

Guerlain La Petite Robe Noire

Guerlain Myrrhe & Délires

Miller Harris Couer d’Eté

Ivy

Cool, dark, green: the leaves and the little black berries from this self-clinging evergreen plant can be steam-distilled and turned into a refreshing green fragrance top note, with just a dash of spiciness. The note has a mystical air to it: in the ‘language’ of plants, it’s been linked with prosperity, fidelity, virtue and positivity. Ivy was also carried by women who wanted to attract good fortune. Not bad allusions for a fragrance note, we’d say.

Smell isoeugenol in:

Goutal Paris Eau de Camille

Diptyque Eau de Lierre

Grapefruit

Whoosh! Quite often, especially in Colognes, you’ll get a zesty burst of grapefruit in the very first hit. Sharp, aromatic, refreshing, grapefruit – from the peel of the fruit of the Citrus paradise tree - blends well with other citrus ingredients in the ‘overture’, or top notes, of summery and uplifting scents, blending well with basil, lavender, cedarwood and ylang-ylang. (In aromatherapy, it’s a wake-up oil.) It really is happiness, bottled.

The history of this tangy-sweet citrus is surprisingly short: it’s only been around for 400 years or so, originating in the Caribbean: a natural hybrid between the pomelo and the orange, introduced to Florida in the 1820s. (We love that it’s also known as the ‘Forbidden Fruit’, as well as one of ‘The Seven Wonders of Barbados’!)

Smell grapefruit in:

DKNY Be Delicious

Floris Pink Grapefruit

Marc Jacobs Daisy

Opoponax

A wonderful name for a glorious gum resin ingredient that’s smokey and soft, luminous and sensual all at once. (Some people think it smells like crushed ivy leaves. Others are reminded of angelica, frankincense and celery, while we love this quote from the blogger Boisdejasmin, when she dipped her testing strip into some opoponax: ‘The wave of warm, sweet scent washed over me: it smelled of aged whiskey, mahogany shavings and bitter caramel, but it was also velvety and powdery.’ The resin is extracted from the bark of the Commiphora eyrthraea tree (mostly from Somalia), and is also known as ‘sweet myrrh’. (It’s sometimes spelled opopanax, too, with an ‘a’.)

Opoponax catches alight easily, which explains why it’s been used for incense for centuries: King Solomon apparently regarded opopanax as ‘the noblest of incense gums’. In perfumery, it lends itself most beautifully to Ambrées, working its exotic magic in many much-loved scents.

Here's what perfumer Sarah McCartney has to say about this ingredient: 'I bought opoponax at first just for the name. It’s my new favourite word. I had to see what it was like, then I fell totally in love with it. No one outside perfumery knows what it smells like by itself because to blends to beautifully with other materials. I described it recently as having the consistency of molasses, but they’d never heard of molasses either so let’s say it’s like incense treacle. These resinous materials like myrrh, the Peru and tolu balsams, benzoin, labdanum and opoponax have been around for thousands of years, helping perfumes to stick around for longer, blending with flowers, citrus fruit and herbs. They give perfumes a gentle, deep dark, sensuality. When I take the lid off and sniff, I can’t help letting out a long appreciative mmmmmmmmm.'

Smell opoponax in:

Aloe vera

Many windowsills boast an aloe vera plant, so useful for treating burns (including sunburn) – but outside this cosmetic use, this perennial succulent plant is also – very occasionally - used as a note in perfumery: green, ‘vegetal’, fresh and aquatic.

Smell aloe vera in:

Galbanum

This resin is a must-have for ingredient in the chypre family of fragrances (in a marriage with patchouli, bergamot and oakmoss): rich, green, mysterious, woody. A little dry, but with hints of pine in there, too. It evolves over time and is very complex, and requires a perfumer’s deftest touch – but it’s incredibly valuable to ‘noses’ as a fixative. It works wonderfully in floral accords alongside hyacinth, iris, narcissus, violet and gardenia - and blends well with spices, too.

The gum itself comes from an umbelliferous (umbrella-like) Persian grass, and can vary from amber to dark green. It’s collected from the stems in small drops (‘tears’). Isn’t it hard to imagine that a plant so green and wafty can produce a scent that’s so deep and resinous. Its use in perfumery goes back millennia: galbanum appears in the Old Testament as an ingredient in holy incense, and was an ingredient of the Egyptian perfume Metopian.

Galbanum essential oil is quite different to the gum: intensely green, slightly bitter, earthy. This product of the galbanum plant is used as a top note, instead – and some very famous fragrances (see below) get their character from this VIP perfume ingredient – most notably Chanel’s No. 19. The galbanum used in No. 19 was a very high grade from Iran. When the Iranian revolution broke out in 1979, the oil supply dried up – and Chanel’s perfumer faced the challenge of reworking this iconic scent. These are the types of challenges which perfumers face: the back-stories you can’t imagine, when you un-stopper a bottle…!

The galbanum plant produces the gum resin asafoetida, used in Indian cooking (as well as perfumery), which you can read about here.

Smell galbanum in:

Driftwood

It’s the image of driftwood that this note really evokes – visions of saltiness, seaside, water and lightness. (There’s a touch of mustiness if you smell a driftwood note ‘neat’ from the vial, which perfumers can cleverly round out with other ingredients.) Mostly, this evocative note – conjuring up images of sculptural wood cast ashore by stormy seas, and bleached by the sun – makes its way into men’s fragrances, or light, beach-inspired summery colognes.

Smell driftwood in:

Marc Jacobs DOT

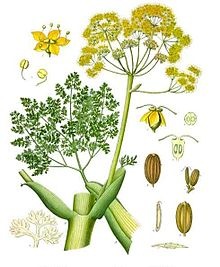

Fennel

Close your eyes and think of aniseed… Or maybe tarragon… Licorice, even… The herb fennel can be used to add a herbaceous, soft, aromatic spiciness to fragrances. (Fennel is of course familiar to most of us as a food – but did you know it’s also used in creating absinthe, the no-longer-banned-but-it-still-makes-you-dance-on-tabletops French alcoholic drink?)

The seeds left behind when the pretty yellow umbelliferous (umbrella-like) flowers have faded are used in steam-distillation of the fennel essential oil. (Those seeds are also chewed, in countries like Pakistan, India and Bangladesh, to freshen the breath.)

Actually, fennel produces TWO types of oil: bitter fennel, and sweet fennel, which can be used as top notes OR heart notes, blending well with lavender, rose, geranium, basil, lemon, rosemary, violet leaf and sandalwood.

Savvy perfumers know exactly which to use to get their desired effect…

Smell fennel in:

Maison Francis Kurdijan Aqua media Forte

Lemon

Lemons and flowers are a perfect marriage, in perfumery. (Think of the way that lemon can ‘cut through’ rich flavours, in cooking, and you get an idea of why the two work so well together.) So while you may be familiar with lemon in Colognes and summer splashes, lemon’s actually present in many, many fragrances.

Its history’s a bit blurry – were lemons first grown in Southern India, or Burma, or China…? But we do know that the Arabs brought this evergreen tree to Europe in around the 8th Century; lemon later made its way to America through seeds carried on Christopher Columbus’s ship, in 1493. The scented oil’s obtained by cold-pressing the peel – and unlike so many other plant ingredients, the aroma that you get from that process is almost exactly the natural scent of the ripe fruit’s peel.

Lemons grow all over the world and are a hugely popular fruit: where would cooking be without lemon’s zest and juice…? Ditto fragrance: it delivers energy, brightness, cheer and refreshment – like sparkling, sweet sunshine, bottled.

Smell lemon in:

Goutal Paris Eau d’Hadrien

Chanel Chance

Chanel Cristalle

Creed Bois de Cedrat

Guerlain Jicky

Guerlain Shalimar

Maison Francis Kurkdjian Acqua Universalis

Miller Harris Fleur de Bois

Grass

Is there anyone doesn’t love the smell of new-mown grass?

Is there anyone doesn’t love the smell of new-mown grass?

Some hay fever sufferers, maybe – but most of us just love the fresh, green scent of grass.

It’s an extraordinary plant – or rather, plants: there are more than 9000 species of grass. (And of course, it’s the major food source for most animals.)

In perfumery, though, grass delivers a sweet, herbaceous scent – maybe not quite like walking past a house where the grass has just been cut, but delivering a gust (or a whisper) of outdoorsy freshness, nonetheless.

Smell grass in:

Guerlain Aqua Allegoria Bouquet de Mai

Cinnamon

Cinnamon is one of the smells of Christmas: spicy and enticing, comforting and sweet, all at once. Our love of cinnamon dates back thousands of years: 2000 years ago the Egyptians were weaving it into perfumes (though it probably originates way before that, in China).

Cinnamon is one of the smells of Christmas: spicy and enticing, comforting and sweet, all at once. Our love of cinnamon dates back thousands of years: 2000 years ago the Egyptians were weaving it into perfumes (though it probably originates way before that, in China).

Cinnamomum verum is thought to have been an ingredient in the original holy ‘anointing oil’, mentioned in the Bible. The Greeks and Romans used it too, often with its near-relation cassia. It’s long been considered to have aphrodisiac properties, when eaten – though if spicy scents turn you on, maybe when dabbed onto pulse-points, too.

Because cinnamon bark oil is a sensitiser – and as such, you may ‘cinnamates’ on perfume packaging, as a warning – where natural cinnamon’s used, it’s likely to have been distilled from the leaves and twigs. But it’s often also synthesised, adding a spicy warmth to Ambrées (and quite a few men’s scents). Here's Andy Tauer on the restrictions on using cinnamon, which he shared with The Perfume Society - and why he loves to use it, all the same:

'Ah... a forbidden fruit, restricted by the EU and IFRA. Sensitising cinnamal, potential allergen. So warm, metallic almost, spicy of course, gourmand, hitting the nose with memories of rice pudding with cinnamon sugar, and making your saliva flow. I love to cook with cinnamon. It brings out the flavors of ginger, onions, adds warmth to the cocktail of exotic flavors from clove, pepper, cumin, fenugreek. In my perfumes, I love it - like a synthetic aldehyde - as it switches the light on, brings out the colours and contrasts. One fine day, in perfumery heaven, we will all smell and enjoy cinnamon in heavy doses: Until then, we have to life with the regulations that we have...'

Smell cinnamon in:

Dior Dioressence

Dior Dolce Vita

Dior Poison

Diptyque L’Eau

Frederic Malle Musc Ravageur

Paco Rabanne 1 Million

Yves Saint Laurent Opium

Orchid

Do orchids smell? Not the ones we now buy in supermarkets, which have become such a popular design statement. But yes, in the wild, some do: the Cattleya orchid, in particular – though even that varies, from heady and vanilla-y to light and clean. (Other orchids - obviously not used in perfumery - can stink of rotten meat, or faeces. The smell is to attract the type of insect that pollinates the plant: some clearly get off on pretty smells, others on stinkers.)

There are thought to be over 20,000 different orchids altogether. The name (who knew?) comes from the Greek ‘órkhis’, literally meaning "testicle", thanks to the shape of the root.

Not terribly romantic, but we do like the Greek myth behind the naming of the plant. So the legend goes, Orchis – son of a satyr and a nymph (quite a combo) stumbled upon a festival of Dionysus (a.k.a. Bacchus), in a forest. As tended to happen at ‘bacchanales’, he imbibed too much, and became somewhat over-amorous towards a priestess. The Bacchanalians tore him apart. His father prayed for Orchis to be restored, but instead the gods transformed him into the flower we know today as the orchid.

In reality, when you smell ‘orchid’ as a fragrance note, today it’s more likely to be synthetic. Nice myth, though.

Smell orchid in:

Dior J’Adore

Jean-Paul Gaultier Classique

Viktor & Rolf Flowerbomb

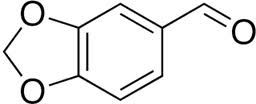

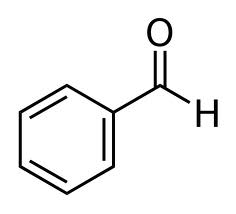

Heliotropin

Technically, heliotropin – the synthetic ingredient which recreates the heliotrope flower – is a member of the ‘aldehyde’ family of chemicals, and was first discovered in 1885.

Here’s the science bit: 1,3-Benzodioxole-5-carbaldehyde, piperonyl aldehyde, 3,4-methylenedioxybenzaldehyde and piperonal are all names for heliotropin. Here’s the non-scientific bit: this synthetic brilliantly copies the powdery, almondy or vanilla-y nuanaces of the beautiful purple, butterfly-magnet heliotrope flower (read about that here).

Like quite a few ingredients, though, heliotrope/heliotropin’s use has been reduced and restricted lately by the International Fragrance Association’s regulations (IFRA for short), and some iconic, heavy-on-the-heliotrope fragrances – including L’Artisan Parfumeur’s glorious Jour de Fête – have sadly been discontinued, as a result.

Smell heliotrope in:

Dior Dolce Vita

Emporio Armani Lei

Guerlain Après l’Ondée

Guerlain Cuir Beluga

Guerlain L’Heure Bleu

Paul Smith London Paul Smith Women

Penhaligon’s Cornubia

Peach blossom

Soft, floaty, feminine: this so-pretty floral note has just a whisper of actual peachy fruitiness about it. Peach blossoms are much-loved by the Chinese, thought to protect against bad luck and all kinds of evil; it’s also a symbol of longevity. Watch out for peach blossom becoming a more popular perfume ingredient, as the influence of the Middle East – which has made for so many ‘heady’ perfumes in recent years – moves East, in response to the dawning love of fragrance among the Chinese.

Smell peach blossom in:

Chanel Allure Eau de Parfum

Dior J’Adore

Guerlain Elixir Charnel Chypre Fatal

Lancôme Trésor

Grape

We eat grapes, we drink them – and sometimes, we dab or spritz a synthesised version on our pulse points. Sugary and sweet, sometimes greener and drier, the note can conjure up the smell of the popular American soft drink Kool-Aid: the same ingredients (methyl anthranilate and dimethyl anthranilate) go into both. As with many fruit ingredients, grapes are having their moment in the sun, thanks to fragrance fashion.

Smell grape in:

Yves Saint Laurent La Collection In Love Again

Iso E Super

Chemicals like Iso E Super (a bit of a tongue-twister, we’ll grant you) are important tools in a modern perfumer’s kit: perfumer Francis Kurkdjian told us it was ‘torture’ for him to create a scent for a recent Paris exhibition, without ingredients like this at his fingertips, to turbo-charge the staying power or help ‘fill a room’. (Many naturals are positively timid on the skin.)

International Flavors & Fragrances, who trademarked Iso E Super, describe it as a ‘smooth, woody, amber note, with a “velvet-like” sensation. Superb floraliser. Used to impart fullness and subtle strength to fragrances.’ On its own, though, it’s sometimes considered almost ‘non-existent’ – which just goes to demonstrate perfume’s magical alchemy, and what happens when different ingredients are blended together. Iso E Super’s said to help ‘personalise’ fragrances, creating an almost bespoke effect when they’re applied to the wearer’s skin. It goes especially well with musks, fruits and flowers.

Iso E Super is very popular in fragrance compositions, even though the International Fragrance Association (IFRA) has rationed its use in a formula, because of its potentially sensitising/allergenic effects. And in just one instance – Escentric Molecules Molecule 01, created by daring contemporary perfumer Geza Schoen – it’s been made the star of the show. Why not sniff that out, and let your nostrils decide what they think of Iso E Super…?

Smell Iso E Super in:

Escentric Molecules Molecule 01

Beeswax

Does beeswax smell? Yes, it does: it’s honeyed, musky, softly sweet and intimate, sometimes with hints of pollen. Natural perfumers – whose palette of ingredients is limited – love it, as it delivers an ‘animalic’ quality yet is cruelty-free, generally harvested from hives that have matured over five years or so, carefully harvested by hand and then extracted using solvents. Beeswax also works brilliantly as a fixative, helping to anchor will-o’-the-wisp, volatile notes.

Smell beeswax in:

Goutal Paris Myrrhe Ardente

Hemlock

You wouldn’t love the smell of hemlock if you got up-close-and-personal – and you’d be unwise to do that, as it’s a seriously poisonous plant: in Ancient Greece, hemlock was the poison used to execute prisoners (including the renowned philosopher Socrates).

Crush the leaves of this frothily-flowered plant, and they smell fetid, rotting – rank, basically. But as with many ‘unlikely’ perfume ingredients, add it in the teensiest dose, and hemlock can add depth and intrigue. (And in similarly teeny does, it’s also been used in medicine as a sedative…)

Smell hemlock in::

Pear

Pear’s so crisp and clean a note, you can almost hear it ‘crunch’. Subtler and ‘greener’ than many fruits, we’d say it was almost made to be garlanded by white flowers, for a spring-like touch.

Pears themselves are a fruit-bowl staple today (though only really satisfying when truly in season, we’d say). And a little background: pear seems to have originated in western Europe, North Africa and eastwards, across Asia. The tree probably gets its name from the Latin ‘pira’.

Pear’s fragrant bounty doesn’t begin and end with its fruits (and subtly powdery blossoms), though. It’s one of the most desirable firewoods, producing a highly aromatic smoke that’s brilliant for smoking meat and tobacco – and which perfumers seek to capture and recreate, quite aside from the delicate crispness of the plant’s much better-known fruit.

Smell pear in:

Issey Miyake Pleats Please

Jimmy Choo Jimmy Choo

Lancôme La Vie Est Belle

Yardley Royal Diamond

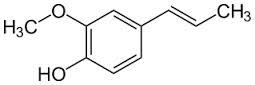

Isoeugenol

Smell carnation in a scent? It’s more likely to be isoeugenol, an ingredient found naturally in the essential oils of nutmeg and ylang-ylang, but which can also be synthesised from eugenol. (Look under ‘E’ for more about eugenol.)

Lily of the valley

The lily of the valley is The Perfume Society’s ‘adopted’ flower: we simply love the French tradition of offering nosegays of this delicate nodding white bloom on 1st May to people you love and admire. (And we’ve adopted it ourselves.) The tradition goes back centuries – to Charles IX, who inaugurated it in 1561. Since then, lily of the valley has also made its way into countless bridal bouquets (including that of Kate Middleton for her wedding to Prince Willliam); in many countries, it’s linked to this day with tenderness, love, faith, happiness and purity.

Almost spicy, so green and sweet, with hints of lemon: that’s lily of the valley – and a more spring-like scent it’s hard to imagine. The flowers themselves are really mean with their oil, though, and synthetics are more often used to recreate lily of the valley’s magic: Lilial, Lyral and hydroxycitronellal are among them.

As well as featuring widely in ‘soliflores’ (so-called ‘single note’ fragrances, which are often actually a lot more complex than that), lily of the valley works its magic in many other fragrances, used to ‘open up’ and freshen the other floral notes in a blend – as a clever writer on the Perfume Shrine blog puts it, ‘much like we allow fresh air to come into contact with a red wine to let it “breathe” and bring out its best’.

Smell lily of the valley in:

Dior Diorissimo

Dior Hypnotic Poison

Floris Lily of the Valley

Goutal Paris Le Muguet

Guerlain Idylle

Woods of Windsor Lily of the Valley

Yardley Lily of the Valley

Apricot

In perfumery, apricot can be lush and sweet – like the fruit – or bitter, like the extract of the apricot kernel (think of an Amaretto-ish bitter almond scent). It’s been used in scent-making almost forever – early Arab perfume recipes recorded by Al-Kindi include the use of apricot. In modern day perfumery the scent of apricot is re-created synthetically, most often for a soft, almost fuzzy fruitiness. Sometimes, alternatively, the scent of the blossom of the apricot tree (a.k.a. Prunus armeniaca) is evoked: pretty, soft and feminine, and a bit ‘floaty’ (just like the white or pink flowers themselves).

Smell apricot in:

Michael Kors Signature

Geosmin

You know that so-distinctive smell when rain falls onto earth…? We’ve been known to stand there, sniffing, for the sheer pleasure of it. Of course there’s no way to capture that smell naturally, so perfumers turn to chemistry to recreate that evocative scent. It can actually be created in nature through the activity of a bacteria called Streptomyces, along with a special enzyme. But mostly, when encountered in fragrance, it’s a synthetic.

Musk

Can a perfume roar? Can it purr? Can it be ‘sex-in-a-bottle’…? If any single ingredient can create those effects, it’s musk. As the excellent fragrance blog Perfume Posse puts it, ‘Musk speaks carnally in whispers or shouts…’ And it’s in almost every scent we dab, spritz and splash onto our skins - because at the end of the day, most of us wear perfumes to feel more alluring…

But musk does more than this. It’s incredibly versatile, in a perfumer’s hands: it softens, balances, ‘fixes’ (adds staying power and keeps a fragrance on the skin, while stopping other short-lived ingredients from disappearing too fast). It smells like skin itself. It almost hypnotises…

And it’s controversial: the original musk came from a sex gland secretion from a specific a species of deer, the Tibetan musk deer, which became endangered - though since 1979 this creature has happily now protected by CITES (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora). Numbers of musk deer dwindled, unsurprisingly, because it took 140 musk deer to produce a kilo of perfume ingredient. But its use goes way back: musk makes its first appearance in the 6th Century, brought from India by Greek explorers. Later, the Arabic and Byzantine perfumers (including the famous Al-Kindi) perfected the art of capturing its aphrodisiac powers, and musk’s popularity spread along the silk and spice routes.