In 1921, a very clever designer and businesswoman created a scent that revolutionised the way women smell. Getting on for 100 years later, Chanel No. 5 is still the world’s most iconic fragrance.

In 1921, a very clever designer and businesswoman created a scent that revolutionised the way women smell. Getting on for 100 years later, Chanel No. 5 is still the world’s most iconic fragrance.

Chanel was truly modern, ‘traversing the boundaries between lady and mistress’, as one commentator put it. She had plenty of ‘racy’ friends – but counted many aristocrats among her circle (including, later, The Duke of Westminster as a lover). She first set up a millinery shop, but by 1921 had a string of successful boutiques in Paris, Deauville and Biarritz. She drove around in her very own Rolls Royce, and owned a villa in the south of France. We owe to Chanel our love of sunbathing, too: previously, tans were associated with outdoor manual labour – until Chanel returned from a beach holiday seriously bronzed, and voilà! Suddenly pale wasn’t so interesting.

Chanel wanted to launch a scent for the new, modern woman she embodied. She loved the scent of soap and freshly-scrubbed skin; Chanel’s mother was a laundrywoman and market stall-holder, though when she died, the young Gabrielle was sent to live with Cistercian nuns at Aubazine. When it came to creating her signature scent, though, freshness was all-important.

She decided that a Grasse-based perfumer called Ernest Beaux was the man for the task. Chanel was vacationing with her lover, Grand Duke Dimitri Pavlovich, when she heard tell of a Grasse-based perfumer called Ernest Beaux, who’d been the perfumer darling of the Russian royal family. Intelligent, well-read and erudite, he wasn’t afraid of a challenge. Over several months, he produced a series of 10 samples to show to ‘Mademoiselle’. They were numbered one to five, and 20 to 24. She picked No. 5 – and yes, the rest is history. So legend has it, the fragrance itself was the result of a mistake by Beaux’s assistant, who’d used 10 times the quantity of aldehydes he was supposed to – a family of extraordinary chemicals which almost propel a fragrance out of the bottle, so your nostrils almost experience it as a champagne-like ‘fizz’. And one particular aldehyde smells clean, a touch soapy, like the scent of a hot iron on linen – which was always going to appeal to Chanel…

She decided that a Grasse-based perfumer called Ernest Beaux was the man for the task. Chanel was vacationing with her lover, Grand Duke Dimitri Pavlovich, when she heard tell of a Grasse-based perfumer called Ernest Beaux, who’d been the perfumer darling of the Russian royal family. Intelligent, well-read and erudite, he wasn’t afraid of a challenge. Over several months, he produced a series of 10 samples to show to ‘Mademoiselle’. They were numbered one to five, and 20 to 24. She picked No. 5 – and yes, the rest is history. So legend has it, the fragrance itself was the result of a mistake by Beaux’s assistant, who’d used 10 times the quantity of aldehydes he was supposed to – a family of extraordinary chemicals which almost propel a fragrance out of the bottle, so your nostrils almost experience it as a champagne-like ‘fizz’. And one particular aldehyde smells clean, a touch soapy, like the scent of a hot iron on linen – which was always going to appeal to Chanel…

As Chanel said later, ‘It was what I was waiting for – a perfume like nothing else. A woman’s perfume, with the scent of a woman.’ After that aldehyde ‘rush’ came notes of precious jasmine, rose, vanilla and sandalwood – but it also smelled ‘abstract’, with no dominant note that perfume-wearers could really make out, from the 80 in its composition. but the success of No. 5 was never just down to its astonishing beauty, but to Chanel’s savvy marketing ploys. She invited a group of friends, including Ernest Beaux, to dinner in a restaurant on the Riviera – and sprayed the perfume around the table. Every woman who passed stopped in their tracks and asked what the fragrance was, and where it came from.

Quite a few of the enduring ‘classics’ of today were actually created in the 1920s and 30s. Working women had developed a new self-confidence, and they wanted to express it through perfume, as well as flapper dresses (and cigarette-smoking…) This was a time of intense creativity. Jeanne Lanvin was a contemporary of Chanel’s, and – like her – began as a milliner and seamstress, founding her own millinery fashion house at Rue du Marché Saint-Honoré. Gradually, the addresses of her shops became ritzier, until the House of Lanvin landed up at 22 Rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré – which remains the address of Lanvin’s Paris flagship today.

Quite a few of the enduring ‘classics’ of today were actually created in the 1920s and 30s. Working women had developed a new self-confidence, and they wanted to express it through perfume, as well as flapper dresses (and cigarette-smoking…) This was a time of intense creativity. Jeanne Lanvin was a contemporary of Chanel’s, and – like her – began as a milliner and seamstress, founding her own millinery fashion house at Rue du Marché Saint-Honoré. Gradually, the addresses of her shops became ritzier, until the House of Lanvin landed up at 22 Rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré – which remains the address of Lanvin’s Paris flagship today.

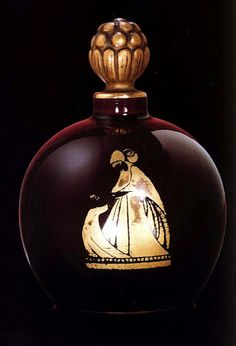

Lanvin’s daughter was her inspiration for the fragrance Arpège. It was conceived for the 30th birthday of her daughter Marie-Blanche (born Marguerite di Pietro), and took its musical reference name from a comment Marie-Blanche made on being shown the first sample, created by perfumers André Fraysse and Paul Vacher: ‘It smells like an arpeggio would’. The spherical black-and-gold bottle was a nod to their love, too, with its silhouette of a mother dressing her daughter (designed by Paul Iribe) – still so recognisable today…

Another 1920s blockbuster – pre-dating even No. 5 – was Guerlain’s Shalimar. The Champs-Élysées-based perfume house had continued their tradition of launching rich, sumptous Ambrées with this fragrance from Jacques Guerlain, with lashings of the newly-popular synthetic vanillin. (It prompted Ernest Beaux himself to comment: ‘When I do vanilla, I get crème Anglaise; when Guerlain does it, he gets Shalimar!’) Guerlain loves to conjure up a love story for their perfumes; this is said to be inspired by the Shalimar Gardens in Srinagar, part of which was laid out by the lovesick Emperor Shah Jehan, in 1619, for the delight of his wife Mumtaz Mahal (meaning ‘Jewel of the Palace’). When she died in childbirth, three years after Shah Jehan took the throne, he build the Taj Mahal in her honour, in Agra. This romantic tale struck a chord in the 1920s, when many eyes in the West were looking to the Orient for inspiration in the arts…

For Jacques Guerlain, vanilla was a powerful aphrodisiac. He’d already used it in Jicky, and this time, fused it with uplifting lemon and bergamot, night-blooming flowers of heliotrope and jasmine, iris, patchouli, and other famously velvety base notes, including benzoin, ambergris, tonka bean, incense, vetiver, sandalwood and musk. Jacques passed that love on to his great-grandson Jean-Paul Guerlain, who’s said: ‘He taught me how to love vanilla, as it adds something wonderfully erotic to a perfume. It turned Shalimar into an evening gown with an outrageously plunging neckline.’

For Jacques Guerlain, vanilla was a powerful aphrodisiac. He’d already used it in Jicky, and this time, fused it with uplifting lemon and bergamot, night-blooming flowers of heliotrope and jasmine, iris, patchouli, and other famously velvety base notes, including benzoin, ambergris, tonka bean, incense, vetiver, sandalwood and musk. Jacques passed that love on to his great-grandson Jean-Paul Guerlain, who’s said: ‘He taught me how to love vanilla, as it adds something wonderfully erotic to a perfume. It turned Shalimar into an evening gown with an outrageously plunging neckline.’

They were glory days, for perfumery globally. But at the end of the 1920s, turbulent times were ahead for the world – and as ever, fragrance would echo, and be influenced by, world events. Read about them here…