Queen Victoria was ‘not amused’ by plenty of things, including the over-lavish use of fragrance. Anything too ‘sexy’ – along with the use of cosmetics and wearing of make-up – was associated with ‘fallen’ women, prostitutes, those of questionable morals. (Even later in Victorian times, when make-up tiptoed back into fashion, it was always natural-looking: a healthy, pink-cheeked look rather than the decadence of a fully made-up face, which was still seen as sinful.)

Queen Victoria was ‘not amused’ by plenty of things, including the over-lavish use of fragrance. Anything too ‘sexy’ – along with the use of cosmetics and wearing of make-up – was associated with ‘fallen’ women, prostitutes, those of questionable morals. (Even later in Victorian times, when make-up tiptoed back into fashion, it was always natural-looking: a healthy, pink-cheeked look rather than the decadence of a fully made-up face, which was still seen as sinful.)

Most fragrances in early to mid-Victorian times were delicate and floral. They were understated, feminine – and often simply conjured up the scent of a particular flower, such as jasmine, lavender, roses, honeysuckle… Aromatic herbs might be used, too: marjoram, thyme, rosemary, and the odd sprinkling of spice – like cloves (which gave a carnation-like scent).

Victoria was a devotee of the (then) British perfume house Creed. Creed actually presented Victoria with a suprisingly heady scent, in 1845, ‘Fleurs de Bulgarie’, which she wore throughout her illustrious reign: a waltz of Bulgarian rose, musk, ambergris and bergamot (and an updated version is still a bestseller today). In 1885, Victoria granted Creed a Royal Warrant, the public acknowledgment of her patronage.

Victorians had a deep love for violets. Violet scents were incredibly popular in Victorian toiletries. They ate violets, candied, in cakes and pastries, and violets were at the heart of the cut flower boom: violet-sellers would stand on street corners, selling nosegays and bunches which women pinned to their dresses, or men tucked in their hat brims or wore on their lapels. And Victorian women – who were big on that so-feminine hobby of flower-pressing – pressed violets into scrapbooks, picked on leisurely country walks through woods where violets flourished.

Victorians had a deep love for violets. Violet scents were incredibly popular in Victorian toiletries. They ate violets, candied, in cakes and pastries, and violets were at the heart of the cut flower boom: violet-sellers would stand on street corners, selling nosegays and bunches which women pinned to their dresses, or men tucked in their hat brims or wore on their lapels. And Victorian women – who were big on that so-feminine hobby of flower-pressing – pressed violets into scrapbooks, picked on leisurely country walks through woods where violets flourished.

By the end of the 19th Century, British fragrance really was interesting again. Among the well-known scents Victorians dabbed (probably still delicately) onto their pulse-points were names like ‘Mille Fleurs’, ‘Jockey Club’ and ‘New Mown Hay’. What’s more, different pharmacists each had their own versions of these scents, because perfumery wasn’t governed by trademark law.

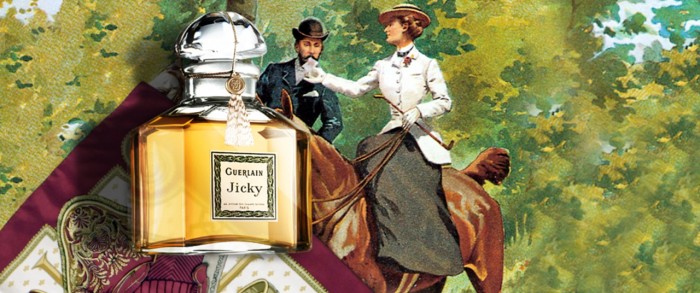

And across the Channel, perfumers began to work on the first fragrances which blended naturals and synthetics. Paul Parquet created Fougère Royale for Houbigant (big on coumarin, that one). And in 1889, Aimé Guerlain reached for the vial of vanillin while conjuring up the Guerlain‘s legendary Jicky – the forerunner of the sublime, sensual, sometimes smouldering scents to come. When it firs appeared, the hint of animal was shocking and unexpected. But through its influence, perfume was about to change dramatically…

Click here to read about fragrance in the early 20th Century…